- Home

- Anne Hampson

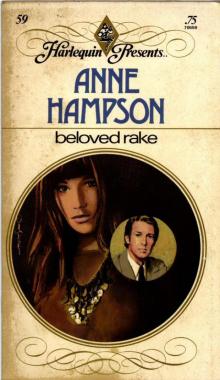

Beloved Rake

Beloved Rake Read online

BELOVED RAKE

ANNE HAMPSON

Although she had spent all her life in Greece, young Serra Costalos was only half Greek — and she couldn't endure the thought of the cold-blooded, arranged Greek marriage that was all that was in store for her.

In fact, she had already run away from home when, quite by chance, she met the Englishman Dirk Morgan and discovered that he was looking for a wife. But a wife with a difference. Dirk had to marry in order to inherit a fortune, and, as he was a self-confessed rake and had no intention of changing his ways, he wanted a wife who would leave him alone and not make a nuisance of herself.

So Serra and Dirk married. But neither of them got what they expected.

CHAPTER ONE

She had run away—away from her father and authority and the handsome young Greek whom her father had chosen as her husband. She had only been told he was handsome, for as yet she had not set eyes on him. They were all there now—Father and Aunt Agni, and Phivos and his parents—discussing the dowry while she, Serra, was all alone in an adjoining room—or she should have been—awaiting the verdict of Phivos’s parents. If all was settled to everyone’s satisfaction then her father would come for her, with the intention of introducing her to her future husband.

What a shock they would all receive! But Serra’s satisfaction was short-lived; she had run from them, but where could she go? Like bees when they swarm she had rested not far from her home before making the second—and final—flight into freedom. A three-drachmae bus ride had brought her from her father’s flower-bedecked villa outside Athens to the Acropolis, where she sat, on one of the marble steps forming the base of the Parthenon, the world’s most spectacular and famous building. Her knees were drawn up, her chin resting forlornly in her hands. She gazed with unseeing eves at the camera-snapping group of people listening in awe-struck wonderment to the guide who, in husky tones, was giving them a brief outline of the history of the site. No one took the slightest notice of Serra, sitting there alone on the steps of the great Temple of Athena, and she wallowed in her misery quite undisturbed. What was to be done? Vaguely she had England as her objective, because her mother had been English—that was why Serra spoke the language so well, with the merest trace of an accent which an English lady had once described as delectable. England, and freedom. If she ever did get there what a time she would have! After the restrictions she had endured since her mother’s death, Serra felt she would just go on and on having her fling. A deep sigh, and a hand stealing to the pocket of her skirt. Two hundred drachmae ... rather less than three English pounds.

Suddenly she swallowed the saliva collecting on her tongue, aware that her inside held half a dozen caged butterflies, but aghast at the idea that she was about to be sick. Sick—not here on the steps of the Parthenon! It would be sacrilege! The little knot of people were some distance away now, and she would not be seen, but ... Unsteadily she rose to her feet, but her legs felt like jelly.

‘Sit still a moment,’ begged a lively male voice, and Serra glanced up to see a young man focusing a camera on her—or so it would seem. ‘It’ll help to fix the perspective.’ He was taking the temple, she realized.

‘I c-can’t—’ A hand went to her mouth; she wondered if she looked as green as she felt. ‘I’m g-going to be s-sick!’

‘How revolting!’ Another voice, deep and cultured and edged with a sort of pained inflection. ‘Better leave your picture until another time, Charles.’ The man made to walk away.

‘No—wait, Dirk—the child’s ill—’

‘My dear Charles,’ drawled the voice, ‘not again! Wherever you go you seem to find a damsel in distress, as you so cheerfully term them. Come on, the picture can wait.’

‘Perhaps, but the girl—’ He looked down at her. ‘I say, are you really going to be si— Er—do you feel dreadfully ill?’

Serra nodded, managing to flash an indignant glance at Dirk, who was clearly impatient to move on. What a tall man!—and lean and sort of— sinewed—

‘Oh,’ she groaned. ‘Yes, I’m feeling dreadfully ill.’ She swayed slightly and Charles caught hold of her arm.

‘The poodle door’s over there.’ He pointed vaguely. Dirk frowned. Clearly he was becoming exceedingly irritated by his friend’s interest in Serra.

‘Poodle door...?’ She glanced in the direction indicated.

‘You know, the door with the poodle on it,’ Charles elucidated. ‘The poodle is leading a woman along.’

‘Oh...’ Serra nodded, enlightened. ‘Yes, I’ll—’ She stopped and looked appealingly at Charles, her big brown eyes moist, her lip quivering. ‘I don’t think I can get there. Will you turn your head, please?’

‘For heaven’s sake, Charles, come away! The girl wants privacy.’

But Charles had no intention of leaving Serra. Passing her a huge handkerchief, he spoke soothingly to her, at the same time leading her away from the steps. His frank round face was troubled, his eyes shadowed. But they had barely taken half a dozen steps when Serra exclaimed in relief,

‘It’s gone off me now!’ She still felt green, but her stomach had settled. ‘I’m awfully sorry; it was the anxiety. You see, I’m in trouble.’

‘You—’ Charles’s eyes moved automatically over her slender figure. Dirk’s eyes made a similar move.

‘Not what you think, Charles,’ he drawled. ‘Greek girls never do.’

‘Never?’ Charles’s eyes opened wide. ‘Then how—’

Serra interrupted, oblivious of what the conversation was about.

‘I’m not Greek. My mother was English.’

‘Was?’

‘She died three years ago, when I was fifteen.’ She gave a little gulp, but was relieved to find it was nothing serious. Thank goodness she wasn’t going to be sick, after all. ‘I’ve run away from home,’ she informed them, directing her gaze at Dirk to see what effect this dramatic piece of news would have on him. Stifling a yawn, he said,

‘Are you expecting our congratulations? Running away from home is the done thing these days, isn’t it?’

‘Not with Greek girls,’ she retorted indignantly.

‘You’ve just said you’re not Greek,’ Charles reminded her, and his friend gave an audible sigh of impatience.

‘My father is, and that’s why I’ve run away. He’s always choosing husbands for me—’

‘Always?’ cut in Charles, frowning. ‘Do you have more than one husband in Greece?’

‘Don’t be silly, of course we don’t!’ She stopped and glanced at Dirk. Why did he appear so bored? He didn’t seem at all sympathetic about her terrible plight—not like his nice friend, Charles. ‘Father chose one boy for me last year and I refused to meet him, then a few months ago he chose another, and I wouldn’t meet him either. But this time Father said I must marry Phivos, and they were arranging it when I ran away.’ Encouraged by Charles’s interest, she went on to explain the procedure, ending by saying that had her mother been alive the situation would not have arisen because her mother had always promised that Serra should find her own husband.

‘Well,’ said Charles after a little pause during which he digested all this, ‘I don’t blame you for running away. Have you decided where you’re going?’

‘I want to get to England, but I’ve only got two hundred drachmae.’

To her surprise Dirk’s eyes suddenly kindled with amusement, and he appeared slightly interested now, although he made no comment on this astounding admission.

‘You’ll not get far on that.’ Charles shook his head. ‘I should go back home if I were you.’

Serra made a feeble protest by shaking her head and Charles then asked what she had against this young man her father had chosen for her.

‘I don’t really know,�

�� she frankly admitted, ‘because I’ve never seen him, but I didn’t like his voice.’

‘His voice?’ Dirk spoke at last. ‘That’s nothing.’

‘You have to live with your husband’s voice,’ she pointed out. ‘Just imagine listening all your life to a voice that grates on your nerves. You have a beautiful voice,’ she added irrelevantly.

Charles grinned, but Dirk maintained an impassive countenance. She examined him for a moment. He was extraordinarily handsome, she decided without any hesitation. Lean features with faintly hollowed cheeks; clear-cut lines to a jaw that was rather too stern and set. Still, she mused, he did seem to have features that went together, as it were, and the whole was most attractive despite the slight austerity that looked out from his piercing brown eyes. His bearing had arrested her from the first because it reminded her of the mental picture she had drawn of the English aristocrat. Her mother used to tell her about these people, and how they lived in mansions standing in magnificent grounds and had lots of servants to wait on them. Serra wondered if Charles and Dirk belonged to this exalted class. If only she could get to England! It must be a most exciting place in which to live. And the freedom—oh, what a time she could have!

‘Will you help me to get to England?’ The question seemed to come from nowhere—for Serra could not believe that she had asked it, not of a complete stranger.

‘Me?’ Emphatically Charles shook his head. 'You must go home, little girl.’

She nodded bleakly.

‘If only an Englishman would offer for me,’ she sighed. ‘I think my father would be only too glad to let me go, for he said only yesterday that if I refused Phivos he’d never get me off his hands because no one else would ever offer for me.’ She looked up at Charles, totally unaware of her appeal ... or that her words had sparked off an idea in Charles’s mind. ‘You see, it’s already all over my village that I’ve refused two—well, it’ll be three now—and they’ll all be saying I’m too proud and so no one will allow their son to offer for me.’

‘Charles,’ said Dirk, bored by this pathetic story, ‘do you move on with me or do I return to the hotel alone?’

‘Are you going?’ The low-toned question was directed at Charles, but Serra was looking at his friend. He wasn’t nice at all, she thought. So superior and aloof. How had a charming young man like Charles come to choose him for a friend?

‘Are you on holiday?’ she asked, handing back the handkerchief to Charles.

‘Just beginning it,’ he smiled. ‘We’re here for a week and then we’re going on to Beirut.’

‘You must belong to the rich English?’ Serra was trying her best to keep them with her a little while longer, for she was becoming more and more frightened of what she had done, and the company kept her from falling into total abject misery. To her surprise her words had a remarkable effect on both Charles and Dirk, who exchanged glances that could only be described as exceedingly strange. ‘Have I said something wrong?’ she inquired apologetically. Charles shook his head, but seemed suddenly to become lost in thought. ‘Oh, dear,’ groaned Serra, putting a hand to her stomach. ‘The—the poodle door!’ She started to run, aware that Charles was calling after her; vaguely she heard him say,

‘We’ll wait for you—by the little temple over there. Nike, I think they call it.’

In less than ten minutes Serra was standing by the Temple of Nike, feeling utterly lost. They had gone— and she had been as quick as she could. But she had known that nasty Dirk would take this opportunity of getting his friend away from her. For about five minutes she walked about, searching for the two men while fully convinced that Dirk had forced Charles to hurry off so that they would never see her again. She would have had to go home in any case, she thought, but if only they had stayed with her a little while longer. It was so exciting to be free to talk to a man as she had talked to Charles, even though she knew that, should she be seen by anyone in her village, she would be ruined for life, because in Greece a girl must never be seen with a man before her marriage. But she had not been afraid; no one in her village would be here. This place was for the tourists, and many of the natives had never even seen it—except on picture postcards, of course, because they were on sale everywhere.

Serra had been wandering away from the temple, walking aimlessly as she thought of the two men and of her problem and of England, where she longed to be. And it was with faint surprise that she found herself near the Erectheum. She sat down on some stones, biting her lip hard because the tears were very close.

Voices! Suddenly alert, Serra sat straight up and looked over her shoulder. But the two men were sitting round the corner from her, out of sight. Their voices reached her plainly. Dirk sounded impatient as he said,

‘I had an idea what was in your mind the moment she mentioned the rich English—’

‘I knew you did; I could tell by the way you looked at me.’

‘Well, as I’ve said, if you want the girl rescuing you can rescue her yourself.’

‘You’re crazy! Here’s the answer to your problem, being handed out to you on a plate, and you ignore it.’

‘You seem to be forgetting Clarice.’

‘You know very well you don’t want to marry her. If you did you’d have done it long ago. Why, everyone knows you’re leaving it until the last minute just to see if someone better turns up.’

‘Thanks; you’re not very flattering.’

‘Oh, I know you could have plenty—but not the right sort. They’ll interfere with your freedom; your gay life will come to an end. But just you mark my words, Clarice won’t be any easy-going, docile wife. She’s possessive already, so you can expect trouble in plenty if you marry her. No, Dirk, a meek and timid little Greek girl’s what you want. She won’t interfere or make claims on your time. She’s been brought up to recognize the superiority of man and she wouldn’t dream of stepping out of place. If you marry this child you’ll be able to carry on as you always have; you won’t even know you’re married!’

‘Anyone would think your concern was all for me,’ returned Dirk with a laugh.

‘But of course it is—’

‘Your concern, Charles, is with the damsel in distress. I know you, remember. Your heart’s too soft.’

Serra sat there, dazed by this conversation, but tensed also, and she was aware of the dampness on her forehead and in the palms of her hands, which were tightly clutched in her lap. She had no idea of the true content of the conversation, but she did realize that Dirk had a problem, and that the problem concerned a wife. And Charles was suggesting that Dirk solve that problem by marrying her, Serra. If only it had been Charles who had the problem, she thought dejectedly, then he would not have hesitated to marry her.

‘Perhaps my heart is too soft,’ Charles was saying, ‘but it’s better than having a heart which is too hard.’ Dirk merely laughed again and Charles went on, his voice tinged with anxiety, ‘I wonder if she’s worse than we thought—’

‘I didn’t think anything, Charles,’ intervened Dirk gently.

‘All right, all right,’ from Charles, impatiently. ‘What I was trying to say was, where is the child? Why hasn’t she come back before now?’

‘Gone off home, I expect—back to an irate papa and an affronted fiancé.’

‘I don’t believe it; the child was distraught. Besides, she told you she couldn’t stand the fellow’s voice—she liked yours,’ he digressed, adding that this in itself was an omen. ‘I’m going to look for her,’ he ended, and Serra heard the crunch of stones as he rose to his feet. ‘The poor child might be staggering about, all alone—’

‘I’m here,’ said Serra, hurriedly jumping to her feet. She didn’t want to lose Charles again, at least, not for a little while. ‘You said the Temple of Nike.’ She had moved to the corner of the building; Dirk was still sitting down, but he began to ease himself off the broken column on which he sat. After a moment he was regarding her through narrowed eyes.

‘Isn’t this the

Temple of Nike?’ Charles was asking, casting a vague glance at the caryatids.

‘It’s the Frertbeum.’ Serra’s head was raised to meet Dirk’s searching gaze. He had known this was not the Temple of Nike, she decided. ‘I thought I’d lost you,’ she said to Charles in quivering tones.

‘Mistake. But no harm done.’ Charles stared into her face. ‘White—very white. You’d better come with us and we’ll get you a drink.’

Serra opened her mouth to thank him, but Dirk spoke before he could do so.

‘How long have you been here?’ His voice was clipped and stern-edged. Serra blushed hotly.

‘Not l-long ...’ She tailed off because it was impossible to lie while those piercing eyes were fixed upon her.

‘How much did you hear?’

‘Oh, I say, Dirk,’ protested Charles indignantly. ‘The girl wouldn’t deliberately listen!’

‘She listened to the arrangements being made for her marriage.’

Serra’s head came up at this. The man was downright rude!

‘How much did you hear?’ he asked again, and when she failed to answer he repeated his question. Serra knew she would have to answer in the end, so she admitted she had been sitting round the corner for about five minutes.

Charles looked quite put out by this and glanced from Serra to Dirk, anxiously scanning his face.

‘We must get her that drink,’ he murmured, less buoyancy in his voice now. ‘She’s not fully recovered yet—’ Breaking off, he turned to Serra. ‘What’s your name? I can’t keep saying her and she.’

‘Serra Costalos.’

‘Serra? So your mother didn’t give you an English name, then?’

Serra shook her head.

She liked Serra, was all she said. Her head was aching; she thought it must be nerves, and she felt she might be better for the drink Charles had promised to get her. ‘Are we going to the tavern?’

Charles looked rather uncertainly at Dirk.

‘If you want to go back?’ he began. ‘I’ll take Serra for a drink.’

But to the surprise of both Serra and Charles, Dirk agreed to accompany them to the taverna.

Dear Stranger

Dear Stranger Dangerous Friendship

Dangerous Friendship Wife for a Penny

Wife for a Penny Pagan Lover

Pagan Lover Blue Hills of Sintra

Blue Hills of Sintra After Sundown

After Sundown Man Without Honour

Man Without Honour Unwary Heart

Unwary Heart Dark Avenger

Dark Avenger Anne Hampson - Call of The Veld

Anne Hampson - Call of The Veld Isle of Desire

Isle of Desire Beloved Rake

Beloved Rake To Tame a Vixen

To Tame a Vixen The Way of a Tyrant

The Way of a Tyrant Heaven is High

Heaven is High A Kiss From Satan

A Kiss From Satan Dark Hills Rising

Dark Hills Rising By Fountains Wild

By Fountains Wild Second Tomorrow

Second Tomorrow South of Mandraki

South of Mandraki Waves of Fire

Waves of Fire The Dawn Steals Softly

The Dawn Steals Softly Realm of the Pagans

Realm of the Pagans Fascination

Fascination Desire

Desire Dear Plutocrat

Dear Plutocrat Strangers May Marry

Strangers May Marry South of Capricorn

South of Capricorn Stars of Spring

Stars of Spring Enchanted Dawn

Enchanted Dawn Master of Moonrock

Master of Moonrock Windward Crest

Windward Crest Man Without a Heart

Man Without a Heart